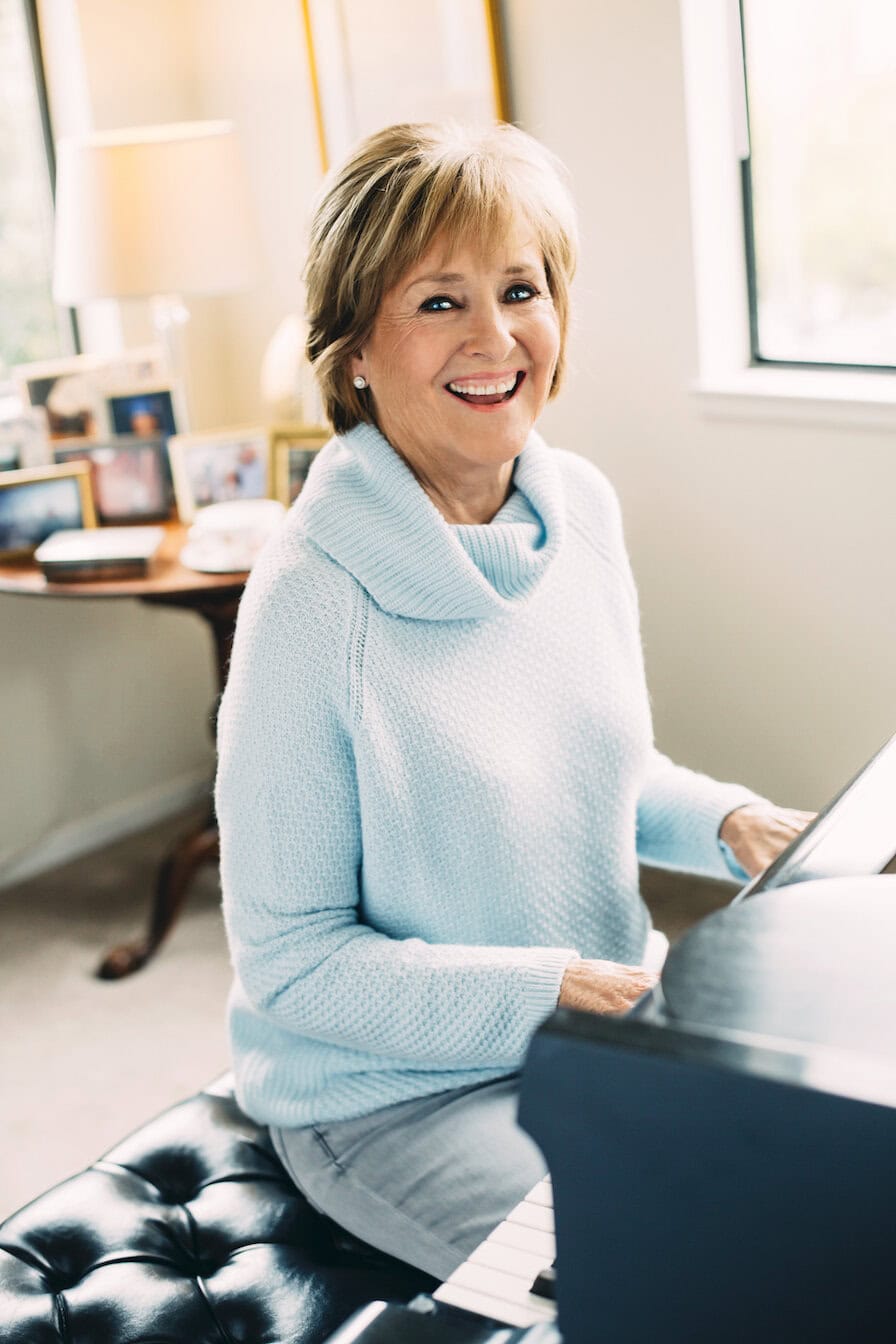

It has been almost 12 years since Frederica von Stade graced the cover of Classical Singer magazine. Since then, she has been hard at work creating new roles, teaching, performing, and helping young people from disadvantaged situations. In this latest interview, the legendary mezzo-soprano reflects on an epic career and shares her thoughts about opera today, motherhood, #MeToo, and her advice for an emerging generation of classical singers.

Flicka presented at the CS Music Online Convention, May 25-30. View her class at www.csmusic.info/convention.

“Dazzling.” “Delightful.” “One of the most beloved musical figures of our time.”

Those are just a few of the words that have been used to describe Frederica von Stade. And yet, they somehow don’t even begin to scratch the surface of her artistry and accomplishments—not to mention her accompanying keen wit and down-to-earth demeanor.

Throughout the course of a long and distinguished career spanning five decades, the 74-year-old mezzo-soprano has appeared on the stages of the world’s most prestigious opera houses and celebrated concert halls, from the Metropolitan Opera—where she made her professional debut—to La Scala, Paris Opera, Vienna State Opera, Covent Garden, Glyndebourne, and Carnegie Hall.

She has performed under the baton of the industry’s most influential and esteemed conductors and stage directors, as well as alongside an impressive list of colleagues.

Her voice can be heard on more than 100 recordings ranging from symphonic works to sacred music, opera, musical theatre, art songs, folk tunes, pop, jazz, and even comedy. Her recording catalog has netted her 12 Grammy Award nominations resulting in two wins.

Her television appearances have seen her performing alongside the Tabernacle Choir as part of the opening ceremonies of the Salt Lake City Winter Olympics, as well as appearances with Sir Elton John, Marilyn Horne, Dawn Upshaw, Kathleen Battle, Samuel Ramey, Jerry Hadley, and scores of others.

In 1983, von Stade was awarded by President Ronald Reagan in recognition of her contributions to the arts. With a series of additional accolades, she also received France’s highest honor when appointed as an officer of L’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, as well as having been elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She also holds honorary doctorates from her alma mater at the Mannes School of Music in New York City, Yale University, Boston University, the Cleveland Institute of Music, the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and the Georgetown University School of Medicine.

To what does she attribute such a longstanding, successful, and celebrated career?

“I tell you what,” she says. “It’s good fortune. I had no expectation that I would ever become an opera singer. I had the best manager. I had a wonderful voice teacher early on. And I had a mother who took me to operas when I was young and made sure it was shoved down my throat.” (Laughs.)

Although opera might not have begun at the top of von Stade’s list of ambitions, she knew from an early age that there was something unique about the art form. And while it has taken her from her native New Jersey to Greece, Italy, Washington D.C., New York, and Paris, von Stade today calls the San Francisco’s Bay Area home, along with her husband of 30 years, Michael Gorman.

“Along the way, I made the connections and I found a brilliant voice teacher,” she says. “I somehow learned how to make a career.”

A Budding Interest Blossomed on a Dare

Born on June 1, 1945, in Somerville, New Jersey, von Stade was the product of a musical family—her father playing the piano and singing, her brother singing in a chorus, and her mother with an ear to her beloved operas on the radio.

With von Stade’s father having been killed in action while serving in Germany shortly before her birth, von Stade’s mother—who called her “Flicka,” Swedish for “little girl” and a nickname that would stick throughout von Stade’s lifetime—instilled a sense of culture.

“My first exposure to opera came when I was 15,” von Stade says. “My mother, brother, and I took a trip to Europe to visit Salzburg and we had a fabulous time. I saw Christa Ludwig perform in Der Rosenkavalier and I’ll never forget it. It was unbelievable. That was my first opera.”

Despite a memorable first impression, it would take time for the art form to firmly take hold of young Flicka.

Upon entering adulthood and paying visits to New York City, von Stade became taken with Broadway musicals and could often be found singing contemporary melodies she had picked up by ear. It was on a $50 dare that von Stade auditioned for the Mannes School of Music as a voice student.

With a raw talent and the potential to hone it, she was accepted.

“I couldn’t read music,” von Stade admits. “But I was hopeful that by joining an opera program I’d learn how. I also discovered that opera also was this whole different use of the voice. And that fascinated me.”

Working with voice teacher Sebastian Engelberg at Mannes School of Music, von Stade swiftly excelled, eventually summoning enough confidence to enter the Metropolitan Opera’s recruitment competition, where she advanced as a semi-finalist and landed a contract as a comprimario artist.

“He taught me how to sing—really sing,” von Stade says of Engelberg. “He also taught me that the best singing was singing that came from the bottom of the heart. That always stayed with me.”

She made her professional debut at the Metropolitan Opera in 1970 as one of the three boys in Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte, followed by a series of additional comprimario roles.

“You’d only sing maybe three or four notes at first—then move on to get to sing 11 or 12 notes—but it was nice,” she says with a laugh. “I was just so grateful for the opportunity.”

Unlike today’s operatic marketplace, where Young Artist Programs have a heavy hand in preparing emerging young singers for professional careers, von Stade says she learned simply by exposure and watching great artists as they worked.

“I was just lucky to be able to be on the same stage with these incredible artists,” she says. “There were no Young Artist Programs back then, so I just watched. What they could do and how they approached the work was so impressive. I learned so much.”

From there, there was no going back.

An Illustrious Career

Throughout the course of the next five decades, von Stade would graduate to larger roles, marking 30 years with the Metropolitan Opera in 2000 and originating new works written specifically for her.

In trouser roles, she became best known as Cherubino in Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro, Octavian in Strauss’ Der Rosenkavalier, and Hänsel in Humperdinck’s Hänsel und Gretel.

Some of her signature roles would become Dorabella in Mozart’s Così fan tutte, Rosina in Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia, Adalgisa in Bellini’s Norma, Mélisande in Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, Marguerite in Berlioz’s La damnation de Faust, and the title roles in Fauré’s Pénélope and Rossini’s La Cenerentola, among others.

From the Metropolitan Opera, von Stade would make her debuts at San Francisco Opera, Santa Fe Opera, Washington National Opera, and Houston Grand Opera before going on to appear with every leading opera company and orchestral ensemble throughout the world.

She also would land her first opportunity to record—Haydn’s Harmoniemesse, conducted by Leonard Bernstein—before spending time developing her career abroad, appearing at Glyndebourne, the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden, the Vienna State Opera, and La Scala.

“I was all over,” von Stade says.

While it was thrilling and rewarding, it also took precious time away from her growing family—something von Stade wasn’t fond of at the time.

In 1973, von Stade married bass-baritone and photographer Peter Elkus, whom she met while at Mannes School of Music. Their union resulted in two daughters—Jenny, born in 1977 and Anna, born in 1980.

“I was lucky—so lucky—for my career,” von Stade says. “But looking back, the one thing I wish I would have done was worked harder. Once my girls were born, I guess you could say that I kind of lost interest in it.

“For a while, I didn’t think that I could have children. So when I did and when I’d get to come home to see them, I was just so excited. But then, I’d have to go away again. It was torture to have to leave. I really just wanted to be with them.”

Motherhood for her also came during a time in opera when attitudes about pairing a singing career with family life were gaining a fresh perspective—something that was long overdue, von Stade says.

“I think that’s a part of my generation that I’m the proudest of,” she says. “We made it OK to be singers and to be women who were singers who wanted to have children and who wanted to work.

“And because of that, most of us did have children. And most of us did work. That’s the best thing that ever happened, because I loved singing but I also loved being a mother.”

After years of marriage and musical collaboration, von Stade and Elkus parted ways in 1990. But not long after, von Stade found love a second time around, with Gorman. The couple welcomed their first grandchild in 2010.

The Right Attitude

While the term “diva” occasionally has been known to mean “difficult” or “temperamental,” for von Stade that definition never has seemed to apply. Throughout the course of her career, colleagues and critics alike have described her as humble, personable, and down to earth, exuding joy both onstage and off.

“I think that’s something I got from my grandfather,” von Stade says. “He had this innate sense that it should be easy to be nice to everyone. The same energy you put into fighting someone, you could put into being kind, in any circumstance. By not doing that, you fail.

“I just always had fun in my career. I loved what I was doing. I never had to pretend.”

A Commitment to New Music

Along with putting her stamp on a variety of staple operatic roles in the mezzo-soprano canon, von Stade also has been regarded for her dedication to championing the creation of new works, most notably with composer Jake Heggie.

In 1998, she collaborated with composer Richard Danielpour for Elegies, a work based on letters that her father had written to her mother while serving during World War II. It was through those letters that von Stade came to know her father.

In 2000, von Stade originated the role of Joseph’s Mother in Heggie’s Dead Man Walking with San Francisco Opera. In 2008, she created the role of Madeline in Houston Grand Opera’s world premiere of Three Decembers, a chamber opera penned for her by Heggie. And in 2015, von Stade created yet another role for Heggie as Winnie Flato in Great Scott.

In 2009, she premiered Nathaniel Stookey’s Into the Bright Lights, a cycle of songs set to three poems von Stade had written about aging, singing, and the love she had for her children.

And for composer Ricky Ian Gordon, von Stade appeared as Myrtle Bledsoe in A Coffin in Egypt in 2014.

“So much of modern opera is really exciting,” she says. “What I love about it is that it deals with issues that are pertinent to our lifetime. As a singer, you have to approach this work with a clear heart and make sure that [the operas] are as intellectually accurate as they are musically accurate. The mission is to be able to tell the story of this music.”

#MeToo and Opera

Long shrouded under a cloak of what seemed to be normality in the opera world, the so-called “casting couch” has been called out in recent years through the #MeToo movement, with victims of sexual abuse speaking out in solidarity.

Since becoming a viral movement in 2017 on the heels of sexual abuse allegations against former film producer Harvey Weinstein, who recently was convicted, a growing number of well known operatic figures also have faced accusations of impropriety.

Among them is famed tenor Plácido Domingo, with whom von Stade has shared a close friendship for nearly 45 years along with his family.

Domingo recently issued an apology and took responsibility for his actions after the U.S. union that represents much of the opera world said that investigators found the singer and former general director at Washington National Opera and LA Opera had behaved inappropriately throughout the course of two decades.

To von Stade, while #MeToo has provided an essential platform for victims to speak out, it also has cast a harsh shadow on some of the significant contributions that have been made in music by those accused.

“The ‘Me Too’ movement has really been awful in our opera world,” von Stade says. “It has hurt and destroyed a relationship with a great artist and a great man. It makes me very sad and disappointed because I doubt there will be a chance to honor him when and if he retires, and he deserves so much gratitude. But any movement has its consequences, and I understand this, but the net scoops up things that don’t really belong there.

“I’ll tell you one little story that will forever be in my heart. After Merry Widow at the Met, there was a big dinner to celebrate, and I was at a table with Plácido and [his wife] Marta.

“My father-in-law, Bill, was with us. Bill had Parkinson’s and lots of shaking and he knocked his red wine glass over. He was mortified, and Plácido quickly dipped his fingers in the spilled wine and blessed himself with the sign of the cross and said, ‘Do you know that this brings good fortune to everyone here at the table?’ We all joined him in dipping and crossing. It was the dearest, most lovely gesture of kindness ever, and that has been my experience of Plácido since the day I met him—and Marta, too, and his kids.”

The Future of Opera

While von Stade has participated in several farewell engagements, she is far from hanging up her hat. She has continued to sing on occasion and teach. For CS Music’s online convention, von Stade will adjudicate and teach a pair of masterclasses: one for high school students and one for young artists and emerging professional singers.

While she admires the capabilities and drive of today’s young singers, she also sympathizes with them.

“Opera is very different now, and it’s a challenging time for young singers today,” von Stade says. “There are more singers, and the jobs just aren’t there. So many of these singers have such a devotion to singing and voices that are out of this world.

“It’s hard for them to make it happen. They go into so much debt for their education, then spend so much time cycling through Young Artist Programs. It’s a struggle. They just need to get out there and do it.”

She also has developed a passion for giving back, seeing to it that youth with disadvantaged backgrounds have access and opportunity for quality exposure to music performances and music education.

The organizations she has been involved with include the Sophia Project and the University of California–Berkeley’s Young Musicians Program.

“Many of these kids have never seen or heard classical music,” von Stade says. “Throughout my career, I was always grateful for all the support I received. Music changes lives. To be able to make that possible for others is a gift.”