This article is part of the Fall 2022 issue of Classical Singer magazine. Click HERE to read all of the articles from this issue or visit the Classical Singer Library.

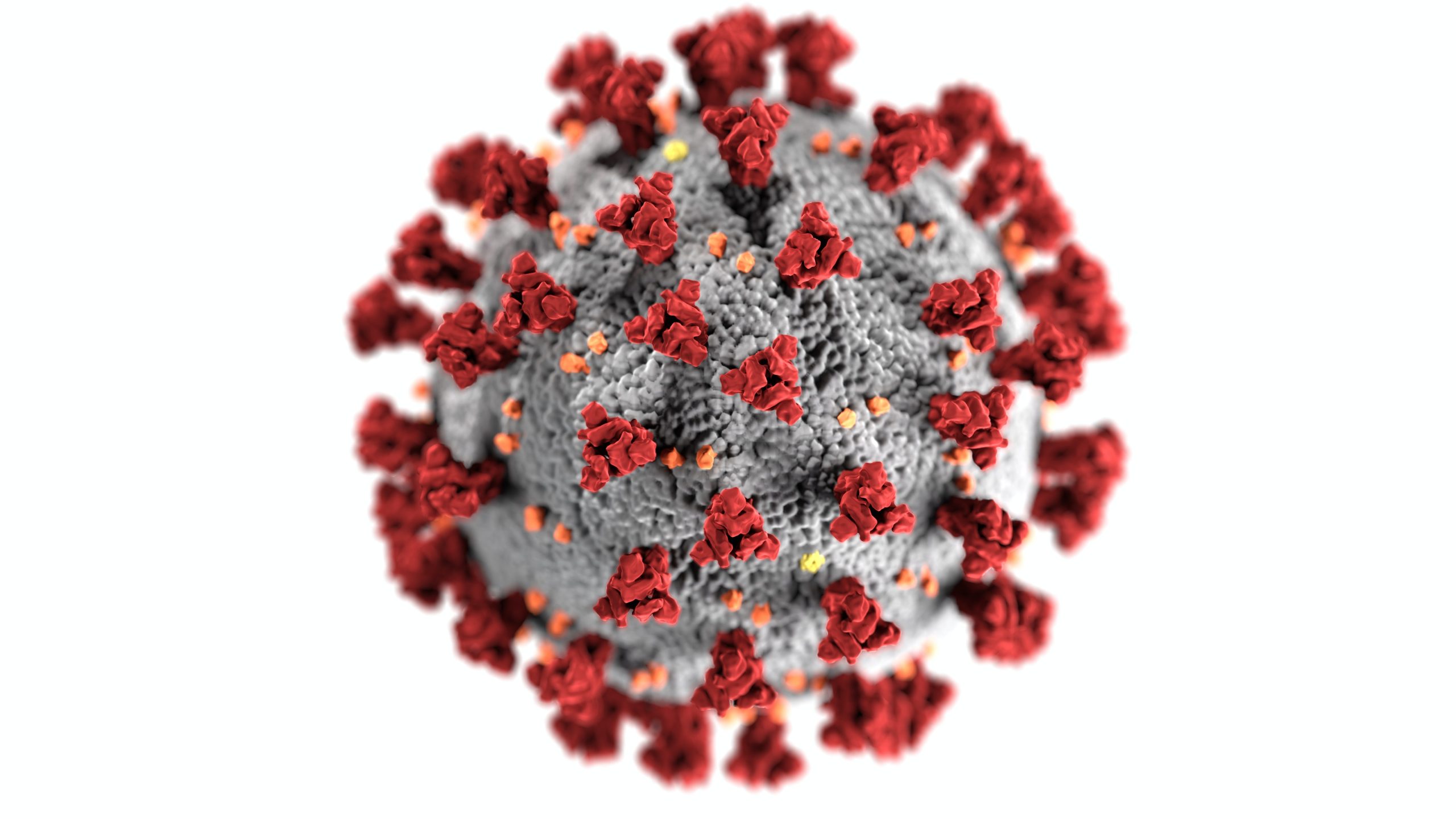

In-person learning is back, but COVID-19 is not gone. Read on to prepare yourself for a return to learning while also minimizing risk for infection and reinfection.

For over 35 years, I have begun the school year with some commonsense advice for students returning to their studies. Many of those columns have been similar, stressing the importance of hard work along with a balanced lifestyle and managing the stress involved in learning, practicing, performing while maintaining a social and psychological anchor in your personal life.

This year is different. Almost three years of COVID-19 have played havoc with the student-teacher relationship. While remote teaching via Zoom is certainly one way to learn, it is far inferior to in-person and hands-on instruction. Teachers are also limited in several ways. They cannot hear everything a student is doing, since the acoustics of a laptop computer do not reproduce the volume, color, and harmonics of a real-life lesson.

Also, many teachers use their hands to feel the vibration of the student’s sound and adjust neck and jaw posture, which are impossible to do through cyberspace—and even the visuals alone require keenly observing the student from the side and the back as well as from the flat frontal image on the computer screen. Also, teachers often sit at the piano and use the keyboard to prompt and accompany their student during in-person lessons.

We don’t as yet know how 2+ years of remote teaching affected the technique and technical development of students, and it would be interesting to hear from teachers what kind of catching up is needed now that lessons are live in the studio.

For the majority who listen to science and have been vaccinated and boostered, the danger of severe or fatal COVID is small, but minor infections are still rather common. These often take the form of a mild cold, with nasal congestion, excess mucus, cough, headache, and a mild fever. Nonetheless, this is still an infection, and you are just as likely to transmit the virus as if you were more seriously ill. So, it is important not to minimize even such minor cases and to follow masking and quarantining mandates.

More potentially significant are the long-term effect of the virus. These can present in many different ways and, since we’re all going through this for only the first time, it is difficult to predict what those symptoms are, how severely they may affect us, and what the ultimate outcome may be. Long-haul effects on the heart and brain have an uncertain outcome—something to keep in mind if you tend to minimize the mild symptoms of a post-vaccination COVID infection.

When I was a medical student 50 years ago, we were taught syphilis was the “great impersonator,” an infection that could present in a myriad of ways. Twenty years later, the same title could have been applied to Lyme disease, with its varied manifestations. And now COVID may fit in the same category.

COVID-19 cannot be eradicated, for several reasons. First, the initial infection may be symptomless for a couple of days. This is the incubation period, when you feel normal but can infect others. Second, the clinical presentation can seem innocuous, like a mild cold or a chill. This is especially the case in those who have been vaccinated and boostered. Even once you have such minor symptoms, it takes a high index of suspicion to decide to get tested. Third, depending on the test and the tester, there is a significant rate of false negativity—and testing and retesting will often change an initial negative into a positive. And, finally, the virus continues to evolve, changing its molecular structure and, with that, its infectivity, severity, and resistance to vaccines.

While these facts seem discouraging, here are some positive aspects. First, if you are vaccinated and boostered, it is much less likely that you will become severely ill. From the virus’ point of view, its success requires that it becomes more contagious but less severe and certainly not fatal. Our immune system, which has evolved over millennia, is constantly learning, and as we don’t overtax it and are generally in good health, it should be able to deal with COVID as it deals with the common cold and the flu.

But let’s get back to school. After a summer of relative isolation, you are back in a classroom or seminar room, singing shoulder to shoulder with other choir members and enjoying communal lunch in the student cafeteria. As you sing, your lungs produce a fine and diffuse aerosol of water particles which persist in the air for extended periods of time. This is where masks come in. While the interstices of a mask are too large to filter out viruses themselves, they do catch the aerosol and trap the moisture (that viruses use as transport) in the weave. I would therefore recommend that you consider wearing a mask whenever you are in close proximity to other students. An N95 mask is ideal, but even an ordinary surgical mask provides a barrier to droplet spread.

As we have watched COVID-19 sweep through the casts on Broadway and in opera, we have come to the conclusion that dropping “the mask mandate” has no scientific basis. While restaurants, airlines, and other venues have triumphantly touted that the crisis is over, this is nothing more than an economically motivated move, driven by the financial hardship of empty theaters and restaurants. We all need to look after our own health by distancing and covering—and, as a bonus, we will also be looking after others as well.

Have a vocal health question you’d like answered? Email support@csmusic.net and see your answer in print! Remember, if you have the question, other singers do as well. Ask away!