This is a monthly column from Juilliard about the nuts and bolts of singing. Search the archives for previous posts.

It’s spring, and at Juilliard we are in the midst of an overwhelmingly rich performance calendar. Solo recitals, orchestra and dance concerts, plays and chamber music—with so much going on, taking time to reflect seems nearly impossible. And yet, reflecting is critical for artistic growth.

For many of you, the past few months have included auditions for undergraduate or graduate programs. Have you reflected on your performance in the auditions? On your growth from audition to audition? On your artistic goals in the larger context of life?

Sometimes such reflecting can be challenging. I write “reflecting” because it is an ongoing process, not a one-time “reflection.” Reflecting takes time and commitment, it’s fluid and sometimes meandering, whereas a reflection is a solid thing that never meanders—although it can sometimes prompt more reflecting.

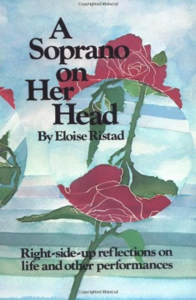

As an artist, and particularly a young artist, it’s nice to have a mentor to help you grow. So, for this article, I went to my bookshelf and found a wise mentor for you. Her name is Eloise Ristad, and the book she wrote is A Soprano on Her Head: Right-side-up reflections on life and other performances. It was published in 1982 (Real People Press, Utah), which may seem long ago, but wisdom has no expiration date.

Chapter 1 introduces the soprano in the title. (Yes, she did sing while on her head—and learned an important lesson about granting herself permission to experiment.) The book also has judges, dancers, checkerboards, clowns, bees, milk, and clammy hands. And so much to reflect upon!

For starters, there are our inner judges. “We give each of these judges a seat of honor in our minds, all the while hating their guts and their never-ending supply of judgments” (p. 10). Throughout the book, Ristad gives us ways to become acquainted with our judges, to laugh at them, to free ourselves from their power, and to turn them into “positive voices.” Reflect for a moment on your inner judges. What messages do they give you? Close your eyes and imagine a conversation with them. Is it possible that your judges have insights for you?

Ristad emphasizes the mind/body connection. She writes, “[T]here are many musicians who are so distant from their physical bodies that they need the drama of actual movement to reconnect them” (p. 27). Ristad suggests several ways to move your body to music, with the goal of reconnecting to your physical body and becoming more alive. And if you feel more alive with your music, your audience will, too. As Ristad writes, “The music moves the listener. But first the music must move the mover—must move the performer” (p. 33). What would happen if—in the privacy of your home—you let yourself move to the music you are studying? Would you feel freer, more in your body? How does connecting your body to your music change the way that the music sounds?

The mind-body connection also is important in the context of stage fright. Rather than looking for a magic formula to avoid stage fright, Ristad suggests that we “play detective and go after some solid information about how your own body responds before and during a performance” (p. 161). She provides a number of ways to identify tension and to understand what is happening when we are struck by stage fright. Ristad’s wisdom is this: “[S]tage fright needs to be confronted and experienced in order to be conquered….If I can permit myself to feel scared, I can also permit myself to reinterpret the scared feelings as excitement, for excitement and fear come from the same adrenalin” (p. 170-171).

How does your body manifest stage fright? Which symptoms did you experience in your recent auditions? What would it be like to acknowledge symptoms as they arise in a performance with a “Hello, nice to see you again”? Would your symptoms become, if not friends, at least familiar acquaintances (rather than saboteurs)?

To read a book such as A Soprano on Her Head is to practice reflecting—to turn inward, to use your powers of thought and observation to learn more about yourself as a person, a body, an artist. As Ristad says, “It takes an act of will to become vulnerable enough to explore scary, unknown territory in our minds and bodies. It takes will power to keep from sliding along in the track someone else makes for us in the snow without realizing when it is time to make our own tracks. It takes will power and courage to suffer the turmoil of change” (p. 199). The act of reflecting arises from that will power and provides the courage for the challenges to come.