Carol Vaness is presenting a Mainstage Masterclass at the CS Music Online Convention on Friday, May 28. View the entire schedule and register HERE.

C

In addition to a monumental career that continues to influence thousands of people, Carol Vaness directly impacts future generations of singers through teaching and mentorship. Since 2007, she has been a professor of music at the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, and is also in global demand as a masterclass clinician and competition adjudicator. Singers are constantly asking her questions, such as “How do I make it?” “What roles should I sing?” and “What if I’m asked to do something I don’t want to do or feel like I can’t?” Now, in light of the near total shut down of the performing arts industry due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there are also questions like “Is it worth it?” and “Will professional singing survive?”

Vaness describes her own career as being started by teachers recognizing and encouraging her natural talent, and then forged by her own nexus to the art form as a means of expression and connection to people. She also acknowledges that each person’s path will be different; there is no one “right” way to make it as a singer. Some will become international stars, some national or regional singers, some full-time voice teachers, and some a combination of these or other things. In any case, she gives her own prescription for singing success.

First, when a singer is recognized by a trusted teacher or coach as one who has the potential for a career, they must then keep these important influences in their life to guide them. In her case, she worked with teacher David Scott well into her professional career. Second, the singer must be willing to do the work. Vaness’ undergraduate voice teacher Charles Lindsley was the one that encouraged her, introduced her to the idea of pursuing singing as a major, and then spurred her on to graduate school. Then, “I was the one who got excited about [singing] and interested by it,” Vaness says.

As an undergraduate, a local paper interviewed Vaness and two other student singers for an article about what it meant to be a singer. According to Vaness, their replies varied “from ‘I’m just happy to sing whenever I can’ to ‘I love it and want to sing some real opera’” to Vaness, who said, “I would give anything to be a singer.” She notes that “there’s a difference” between these answers; in other words, the desire for the career matters. “I practiced hard and I worked”—not only on her voice, but to support her studies. Through undergraduate and graduate school, she had multiple jobs: cleaning floors in the school cafeteria, working in retail, and singing for churches and temples.

But the jobs never stopped her from working on her voice. “In fact,” she says, “at one point my teacher had to tell me, ‘You know you can take a voice rest day, right?’ And I’m going, ‘Do I want to? No!’” Her focus was always on her singing.

“You can’t complain about doing the work for it,” she says. This means extra practicing, taking required languages (“You wait until you’re singing in Italy somewhere and you want to tell a doctor how you feel but you can’t!”), and self-evaluation, which is critical to the singer. “You need not only to hear, but you have to look at yourself relentlessly.” Students may review their lesson videos but only see the things they’re doing well.

Alternatively, they may only see the things they’re not doing so well. “And that,” she says, “is the delicate balance. You have to be willing to, while you’re looking at these things, not just think, ‘Oh my God! That’s so horrible!’ but rather think, ‘Hm, I wonder if there’s something I can do about that.’”

As a teacher, she says, “I never try to change anybody’s sound.” Just as not everyone will have the same career path, not everyone will sing the same roles as others. Keeping in mind that “just because you sing a good Gilda doesn’t mean you’re going to be a good Zerbinetta.”

Singers must be able to identify and work on what their unique talents are—and also what their weaknesses are, because “singers can work on something problematic and it can become an asset,” she says. For example, “A voice that sings sharp can become strahlende (‘radiant’)—it’s amazing what you can become if you work hard enough. The main thing to learn first is how to make a beautiful sound.”

Singers’ work also involves thoughtful consideration of repertoire. “What I want to hear,” she says, “is a student who is not afraid to try. . . . I don’t want to encourage every young singer to run out and find the heaviest thing ever, but I mean, if you’re not inquisitive . . . .”

She also advises, “You have to be sure that when you add on acting that you don’t suddenly add on a lot of problems.” She recalls watching the first telecast ever from the Metropolitan Opera, La bohème, as an undergraduate and remembers comments people made about the singers. “All of a sudden it became clear to me that it mattered how you look [in terms of acting].” Years later, she was told about performances, notably her Don Giovanni telecast from the Met, that everything she did “looked easy. Well, let me tell you, I practiced it that way . . . I probably had a thousand rehearsals on some phrases!”

Ultimately, she says, singers must remember that “it’s about taste—not everybody likes strawberries or chocolate. My sister hated watermelon! I couldn’t imagine. I eat just about everything, except maybe sea urchin . . . but there are people who love it!

“I think it’s important that people understand that you can’t just change your sound for every new conductor, every new opera company—there is no ‘one size fits all.’” But despite judgment and competition from every side, from sound, to appearance, to acting, “There’s a lot to be said about having a competitive nature that isn’t toxic. I’ve always just been in competition with myself, in my own brain, like, ‘I want to do this!’—‘Well, do you think you can do it?’—‘I can do it, I know I can!’”

The drive to succeed in a highly competitive industry has often left young singers vulnerable to unfair demands, harassment, or worse. Vaness comments on her own past experience when offered a role that she particularly wanted to sing. Before she had a chance to accept or decline said offer, a member of that artistic team made an inappropriate advance toward her and, when she refused, she was taken off the contract. (Incidentally, she had decided she would likely decline the offer anyway as the role was too big for her voice at the time.) Regardless, it is unacceptable for anyone to make these types of advances and to hold contracts dependent upon them.

Ultimately, she was given a different role on another contract, and one that was a better vocal fit. In her words, “If someone comes on to you, even if you lose the job, it’s worth it [to refuse].” In her entire career, she never felt the need to do anything except be true to herself, vocally and personally.

Once at the precipice of the professional level, how exactly does a young singing career flourish in an industry already rampant with underfunding, corporate and organizational cuts and, now, pandemics? Many ensembles, both established and new, have taken performances to alternative venues. Performances have been staged in bars, abandoned warehouses, private homes, and even public parks.

Vaness also gave an example of performance opportunities which can be very important for young singers—namely, organizations’ outreach efforts through performances at nursing homes, schools, and other locations. She had many such formative experiences as an affiliate artist with the San Francisco Opera, including at institutions for people with disabilities and the California Institution for Men—a prison in Chino, California. She has also taken her opera workshop classes to local nursing homes in Bloomington, Indiana.

“The main thing is,” she says, “it gives the singer a purpose. I find with young singers—and I don’t blame them—they’re in school studying, doing whatever we’re saying they should do, but at the same time they’re wondering, ‘How’s this [career] really going to work?’ They think, ‘I want to be a great singer. I want to be a star.’ Well, I did outreach, and it helped me, because if you’re ever in a situation where you can really look your audience in the eye, well . . . you can win souls that way.”

Now, with current pandemic limitations of mostly video-recorded auditions and virtual performances, how can singers make that unique emotional connection through performance when we don’t have an audience’s energy or any other humans in the room? “All I have to say to that is when you look at a camera making a recording for some place, you have to sing to that camera as if your life depended on it,” she says. Because when you win the audition, when we are able to get back to live singing then, “You’ll have the chance to be able to make a difference.”

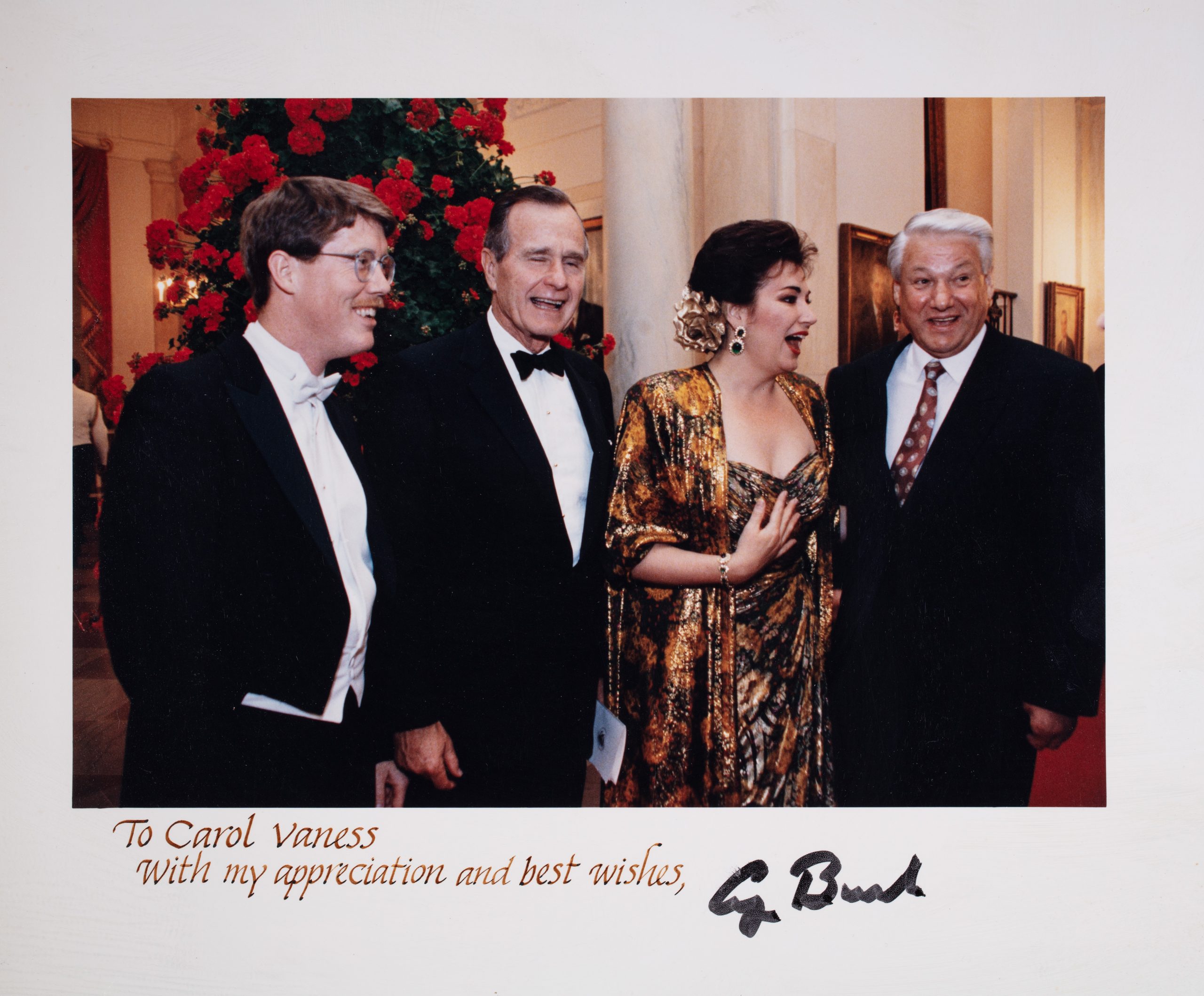

Amid current tensions about why the performing arts and artists are worth government financial support, Vaness gives an example of how performing arts can make an important difference, even in politics. In June of 1992, Vaness sang at the White House after a summit between U.S. President George H.W. Bush and Russian President Boris Yeltsin. They had reached an unprecedented agreement to decrease the number of nuclear warheads in both countries and begin a new “partnership and friendship” between the former adversaries.

Vaness was invited to give the command performance at the ball celebrating the armistice, and as she was singing Rachmaninoff’s “How Fair This Spot” in Russian, she recalls seeing Yeltsin’s wife sitting in her chair weeping and smiling. She shares, “I’m in the White House, getting ready to sing to people, and they say, ‘We have an arms agreement between Russia and the U.S.! Our people can be safe,’ for however long as these gentlemen live. And I was like, ‘Oh, man’ . . . the importance of what they were doing, it was amazing.

“And I was somewhere in the middle of it, singing . . . because singing is so good to reach people. I honestly do think it’s what we are for. I think we’re here for peace. You know, I think the more you have people like us that can sing and bring relaxation in any way . . . we have no idea, honestly, how we have touched people.”

There is no mistaking that a successful career as a singer is now a daunting prospect. For many years there have been company closures, program downsizing, and other industry changes forced by economic reasons and, after being shuttered last year, the performing arts are now struggling to adjust in a new, pandemic conscious world. In a July 2020 Opera America article, Vaness acknowledged the vast numbers of hopeful student-singers coming out of graduate school and facing an industry, she says, “that doesn’t have that many jobs anymore.”

When asked, however, she says, “No, I just don’t think the human race will give up on opera singing. I really don’t. We’ve had a lot more [bad things],” and performances have gone on. Personally, she sees innovation and creativity now not only as a necessity for singing’s survival, but as an exciting and thrilling movement to gain future audiences.

She describes going to some student opera rehearsals last year when all the singers were masked, and it was an opera that had never been a particular favorite of hers. But, “this time I loved it. And the reason I loved it was because every single person was so thrilled to be singing . . . I mean, it was such a great, affirming moment for me seeing that. And what I loved is how they sang, how they presented themselves. It was without fear. It was with joy.”

She says, “Yes,” the singing career “requires a lot of sacrifice” and “there’s a lot of competition.” And, from now on, “there may not be a ‘normal’ as we knew it. But who knows how much more everybody will love it . . . I mean, I know when I hear live music now, I get so moved.

“I think it’s a way to take us back to why we loved it to begin with—because it gives you hope for the world.” If only for a few hours, or even a moment, singing takes people out of themselves, out of their circumstances, to feel a sense of something else, perhaps something greater. And that “is 1,000 percent why I’ve always sung, anyway.”

Endnotes

“Summit in Washington; Bush and Yeltsin Agree to Cut Long-Range Atomic Warheads; Scrap Key Land-Based Missiles” by Michael Wines, the New York Times, June 17, 1992, csmusic.info/RWVJcL.

“Night of the Dancing Bear” by Donnie Radcliffe and Dana Thomas, the Washington Post, June 17, 1992, csmusic.info/3hXxPu.

“The American Singer: 1970 to 2020” by Fred Cohn, Opera America Magazine, July 1, 2020, csmusic.info/L2gz73.